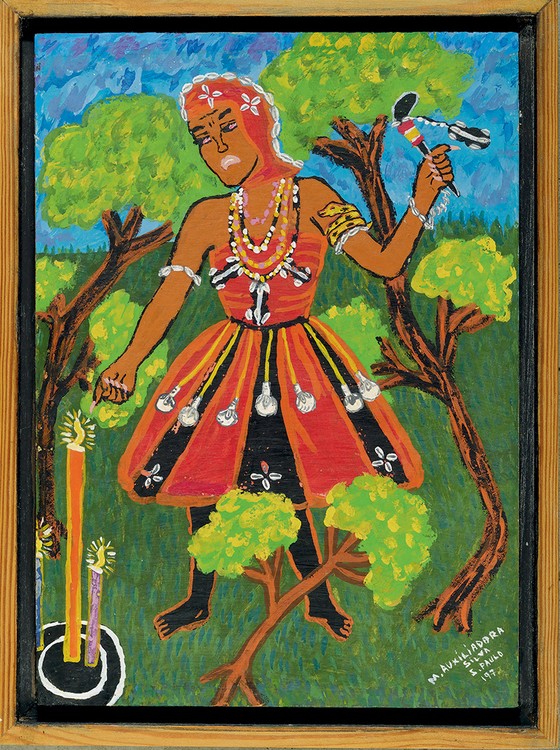

(‘Sem titulo (Exu) – Divulgacao Masp’, por Maria Auxiliadora)

I have always had to allow my mind to be in a contemplative state to write. Any creative task of mine has always implied a meditative mind. Even better, an oblivious mind. That is why it was not a surprise when many years ago, reading Harald Weinrich for my Master’s dissertation I could learn about the potentiality of deep forgetfulness to creation. In Lethe: The Art and Critique of Forgetting the author shows how these two, the dialectical duo forgetting/remembering and creation are interconnected. If I use the Portuguese expression ‘o fio da meada’ (something like ‘a memory thread’) what comes to my mind is always Ariadne’s ball of thread, the one she gave to Theseus to escape the labyrinth in Greek mythology.

This loose association leads to another disjointed assumption: memory helps to escape. As remembering or forgetting, her twin sons (excuse-me, but memory is female). However, escaping from what? From whatever is needed. If it is to escape from the burdens in life, so be it. If it is to escape one’s own fate, it is still valid. And, if it is to escape an enforced silencing in order to fight injustice, excellent.

These two instances, remembering and forgetting, provide highly potent tools for changing destinies. Not for other reasons the archives are apparatus of power, allies of grand societal rulers such as governments, churches, privileged institutions. Official archives in their many and imposed forms decide what to remember and what to forget. In a very rough way, following this line of reasoning, they pretty much decide, then, whether we can escape or not. Nonetheless, are we prisoners?… I did not mean that, I do not remember why this thought is here – perhaps there is something about institutional power that impels us to escape.

This outward labyrinth I am taking you in is Água de barrela’s accountability. Eliana Alves Cruz’s work exposes this tension of memory very well, the remembering/forgetting role in how we deal with our fate. A fractured history which is still unfolding, the Afro-Brazilian past lingers in the present in Brazil like a wounded monster (a Minotaur may come to mind, that’s fine). However, this beast is still alive. And, we know, it is hungrier than ever. The merit of this book then is to offer us a thread. Less mythologically speaking, Cruz takes in the hands of her writing the determination of choosing what to remember or to forget, and how to remember or forget. The author’s decision to dive into her great-aunt memories as a schizophrenic and to collect and assemble, for six years, facts, objects, letters, and to revolve the cultural memories of so many peoples involved in the crossing of the Atlantic is admirable. As are the works of female Afro-Brazilian writers, artists, citizens who, in the last years, have voiced their challenges to past and present archives in order to create a fairer society.

As a student in life I can just consider Água de barrela a piece to be disseminated, to inspire generations, to contribute to the history we are building in Brazil and in the Lusophone Atlantic. The book comes to join this transatlantic movement of knowledge and creativity undertaken by many women lately, which includes the project Women of the Brown Atlantic. Eliana Alves Cruz’s work is necessary, as a chosen act of remembering the humanity we are made of. I hope that in this Memory Residency I am able to highlight this enough.

There could not be a better time to follow this thread.